[摘要] 背景与目的:局部晚期食管鳞状细胞癌(locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma,LAESCC)患者新辅助免疫治疗联合化疗(neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy,nICT)后行根治性手术治疗具有较好的有效性和安全性,能够提高患者的病理学完全缓解(pathological complete remission,pCR)率、主要病理学缓解(main pathologic response,MPR)率及R0切除率。新辅助治疗后达到pCR/MPR的患者预后明显优于未达到pCR/MPR的患者,因此寻找pCR/MPR的预测因素有助于筛选联合治疗的优势人群。本研究旨在探讨nICT前后的临床资料对LAESCC患者nICT后行根治性手术的不同病理学缓解程度的预测价值并观察其安全性。方法:收集2019年1月—2023年6月于川北医学院附属医院在nICT后行根治性手术的LAESCC患者。收集所有患者的临床资料以及新辅助治疗前后患者的部分血液、炎症和营养学指标,根据新辅助治疗后的不同病理学缓解程度进行分组,通过多组比较方差分析及LSD-t事后检验探索对不同病理学缓解程度具有影响的因素,收集并记录患者新辅助治疗期间的不良反应及最终的手术情况。本研究已获得川北医学院附属医院医学伦理委员会批准(伦理审查编号:2024009)。结果:共收集到62例nICT后行根治性手术的LAESCC患者,新辅助治疗期间只有1例患者出现了4级的骨髓抑制表现,其余患者的不良反应均≤2级;手术的R0切除率为98.39%。本研究与川北医学院附属医院既往LAESCC新辅助化疗后行根治性手术治疗的研究相比,在手术时间、术中出血量、术后住院时间及手术并发症等方面未见明显差异。术后的病理学检查结果显示,pCR率为22.58%(14/62),MPR率为40.32%(25/62)。根据术后不同的肿瘤退缩分级(tumor regression grade,TRG),分为TRG1、TRG2和TRG3~4组,3组患者在新辅助治疗前的血小板分布宽度(platelet distribution width,PDW)及新辅助治疗后术前的中性粒细胞-淋巴细胞比值(neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio,NLR)差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。进一步对3组患者在新辅助治疗前的PDW及新辅助治疗后术前的NLR分别进行组内两两比较,发现TRG2组的PDW及NLR均低于TRG3~4组,差异有统计学意义(P <0.05)。结论:LAESCC患者nICT后行根治性手术可以获得较高的R0切除率、pCR率及MPR率且安全性可靠,新辅助治疗前患者的PDW越低、新辅助治疗后术前患者的NLR越低预示着越好的病理学缓解效果。

[关键词] 食管鳞状细胞癌;新辅助免疫治疗联合化疗;根治性手术;病理学缓解程度;安全性

[Abstract] Background and purpose: Radical surgery after neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy (nICT) in patients with locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (LAESCC) has good efficacy and safety, and it can improve the patients’ pathological complete remission (pCR) rate, main pathologic response (MPR) rate and R0 rep rate. The prognosis of patients with pCR/MPR after nICT is significantly better compared with patients without pCR. The prognosis of patients achieving pCR/MPR after neoadjuvant therapy has been demonstrated to be significantly better than that of patients with non-pCR/MPR. Therefore, finding predictive factors of pCR/MPR is beneficial for us to screen out the advantageous populations for combination therapy. The aim of this study was to investigate the value of clinical data of patients with LAESCC before and after nICT in predicting the degree of remission of different pathologies after radical surgery following neoadjuvant treatment and to observe the safety of the treatment. Methods: Data of patients with locally LAESCC who underwent radical surgery after nICT from January 2019 to June 2023 at the Affiliated Hospital of Chuanbei Medical College were collected. The clinical data of all patients as well as some blood, inflammation and nutritional indexes of patients before and after neoadjuvant therapy were collected, and the patients were grouped according to the different degrees of pathological remission after neoadjuvant therapy. Data were analyzed by multi-group comparative analysis of variance (ANOVA) and LSD-t post-hoc test. We explored the factors that had an influence on the different degrees of pathological remission, and collected and recorded the patients’ adverse reactions during neoadjuvant therapy as well as their eventual surgeries. Results: Data of 62 patients with LAESCC treated with nICT who underwent radical surgery were collected. Only one patient showed grade 4 myelosuppression during neoadjuvant therapy, and the rest of the patients had adverse reactions ≤grade 2. The R0 rep rate of the surgery was 98.39%. The present study was compared with the previous studies of LAESCC treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical surgery performed in Affiliated Hospital of Chuanbei Medical College. Compared with the previous studies conducted in our center, no significant difference was observed in terms of operation time, intraoperative bleeding, postoperative hospitalization time and surgical complications. The postoperative pathologic results showed that the pCR rate was 22.58% (14/62), and the MPR rate was 40.32% (25/62). According to the different tumor regression grade (TRG) after surgery, patients were divided into 3 groups of TRG1, TRG2 and TRG3-4, and differences in the platelet distribution width (PDW) before neoadjuvant therapy and the preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) after neoadjuvant therapy were statistically significant among the 3 groups (P<0.05). Further intra-group two-by-two comparisons of PDW before neoadjuvant therapy and NLR before surgery after neoadjuvant therapy were performed for the three groups of patients, respectively, and it was found that the PDW and NLR in the TRG2 group were lower compared with the TRG3-4 group, and the differences were statistically significant (P<0.05). Conclusion: Radical surgery after nICT treatment in patients with LAESCC can have high R0 rep rate, pCR rate, MPR rate and reliable safety, and the lower PDW of patients before neoadjuvant therapy and the lower NLR of patients before surgery after neoadjuvant therapy predict better pathological remission efficacy.

[Key words] Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; Neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy; Radical surgery; Pathological remission degree; Safety

食管癌是一种严重威胁人类健康的恶性肿瘤,食管癌发病率在全球范围内排名第7,死亡率排名第6[1]。食管癌主要分为食管腺癌(esophageal adenocarcinoma,EAC)和食管鳞状细胞癌(esophageal squamous cell carcinoma,ESCC)。在西方国家,EAC是食管癌的主要类型,而在东亚国家(如中国和日本),ESCC约占食管癌患者的90%[2]。2020年全球癌症统计数据[3]显示,中国食管癌的新增患病人数及死亡人数均超过全球的一半。高达40%~50%的食管癌患者初诊时已为局部晚期,单纯手术效果不佳,5年生存率仅为15%~34%[4-5]。因此局部晚期ESCC(locally advanced ESCC,LAESCC)患者的治疗需要通过多学科协作来改善其生存情况,新辅助化疗或新辅助放化疗能显著改善食管癌患者的病理学缓解率及生存情况,日本的JCOG9907研究[6]提示新辅助化疗较单纯手术治疗能够明显提高LAESCC患者的5年生存率[55% vs 43%,风险比(hazard ratio,HR)=0.73,95% CI:0.54~0.99,P=0.04]及病理学完全缓解(pathological complete remission,pCR)率(17%)。CROSS研究[7]中关于ESCC患者的10年生存数据显示,与单纯手术相比,术前加用放化疗(卡铂+紫杉醇,41.4 Gy,23次)获益更大(46% vs 23%,P=0.007)。然而,尽管采取了多种联合治疗模式,但是LAESCC的复发风险仍然很高,因此仍需要探寻新的联合治疗模式。

肿瘤免疫治疗在过去几十年中发展迅速,特别是对于免疫检查点抑制剂(immune checkpoint inhibitor,ICI)的研究。ICI是单克隆抗体,可以通过缓解免疫检查点相关分子产生的免疫抑制作用来抑制肿瘤的进展,并可增强机体的抗肿瘤反应[8]。在KEYNOTE-181、ATTRACTION-3和ESCORT等多项Ⅲ期临床试验[9-11]中,ICI联合化疗对晚期ESCC显示出良好的疗效,带来了显著的临床获益,已被批准用于晚期ESCC的二线及以上治疗。随着ICI疗效受到认可,ICI联合治疗逐渐应用于ESCC患者的围手术期。NICE、ESONICT-1和PALACE-1等临床试验[12-14]结果显示,ICI联合化疗作为LAESCC的新辅助治疗具有良好的安全性和有效性,且能够实现较高的pCR率和R0切除率。已有证据表明,新辅助治疗后的病理学缓解情况是患者生存的独立预后指标[15],新辅助治疗后达到pCR/主要病理学缓解(main pathologic response,MPR)的患者预后明显优于未达到pCR/MPR的患者[16- 18]。然而,并非所有ESCC患者都能从ICI治疗中获益,因此寻找有效的疗效预测标志物有助于筛选新辅助免疫治疗的优势人群。本研究旨在探索哪些临床资料能够对LAESCC患者新辅助免疫治疗联合化疗(neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy,nICT)后行根治性手术后的病理学缓解程度具有预测价值,并观察其安全性。

1 资料和方法

1.1 纳入及排除标准

纳入标准:① 新辅助治疗前均经病理学检查证实为胸段ESCC患者;② 临床分期为T2N+M0~T3-4N0/+M0(ⅡB期~ⅣA期)[参照2018年美国癌症联合会(American Joint Committee on Cancer,AJCC)第8版食管癌TNM分期系统 [19]]且直到新辅助治疗前未发现远处转移;③ 确诊后至新辅助治疗前未接受过任何抗肿瘤治疗。

排除标准:① 免疫系统缺陷或患有自身免疫性疾病;② 正在进行免疫抑制治疗者;③ 肝、肾、骨髓功能异常或伴有其他脏器的器质性损伤;④ 心肺功能异常或无法耐受手术者;⑤ 治疗前有明显感染征象;⑥ nICT不足2个周期者;⑦ 新辅助治疗后未行根治性手术切除者;⑧ 资料不完整。

1.2 一般资料

收集2019年1月—2023年6月于川北医学院附属医院在nICT后行根治性手术的LAESCC患者。根据新辅助治疗后的病理学缓解程度不同进行分组,收集所有患者的临床及治疗相关资料以及新辅助治疗前和新辅助治疗后术前的部分血液学、炎症及营养学指标。本研究已获得川北医学院附属医院医学伦理委员会批准(伦理审查编号:2024009)。

1.3 治疗方法

所有患者共进行≥2个周期的nICT,每3周重复1次。化疗方案为白蛋白结合型紫杉醇/5-氟尿嘧啶(5-fluorouracil,5-FU)+铂类药物,免疫治疗使用程序性死亡蛋白-1(programmed death-1,PD-1)抑制剂,免疫治疗和化疗可以以不同的顺序进行。

化疗方案的具体剂量及用法:

⑴ 紫杉醇类+铂类:

紫杉醇类:白蛋白结合型紫杉醇200 mg/m2,静脉滴注30 min,第1天;铂类药物(以下3种任意1种):奈达铂80 mg/m2,静脉滴注,第1~3天;洛铂50 mg/m2,静脉滴注,第1天;顺铂50 mg/m2,静脉滴注,第1~5天。

⑵ 5-FU+铂类药物:

5-FU 1 000 mg/m2,静脉滴注,第1~5天;铂类药物(以下3种任意1种):奈达铂80 mg/m2,静脉滴注,第1~3天;洛铂50 mg/m2,静脉滴注,第1天;顺铂50 mg/m2,静脉滴注,第1~5天。

免疫治疗方案的具体剂量及用法:

① 信迪利单抗200 mg,静脉滴注;② 替雷利珠单抗200 mg,静脉滴注;③ 卡瑞丽珠单抗200 mg,静脉滴注。新辅助治疗结束间隔≥3周后行食管癌根治性手术,均采用右胸三切口胸腹腔镜联合食管癌切除术,治疗前及治疗过程中完善相关的临床检查。

1.4 根治性手术后病理学标本取材过程

将手术切下来的完整标本进行固定,固定好标本后进行取材,取材时记录切除食管的长度、肿瘤部位、肿瘤距口侧切缘、肛侧切缘及环周切缘的距离、肿瘤大体分型、大小、切面颜色、质地、浸润深度、是否累及食管胃交界部、肿瘤旁或肿瘤周围食管黏膜/肌壁检查所见。自肿瘤中心从口侧切缘至肛侧切缘取下所需食管组织分块包埋,包括肿瘤、肿瘤旁黏膜及两端切缘,对肿瘤侵犯最深处及可疑环周切缘受累处重点取材。对周围黏膜糜烂、粗糙等改变的区域或食管/胃壁内结节及食管胃交界部组织应分别取材[20]。对新辅助治疗后病变不明显的标本,将可疑病变区和瘤床全部取材。将扪及的食管/胃壁外膜的淋巴结及分组淋巴结全部进行病理学检查。

1.5 相关指标的计算方式

中性粒细胞-淋巴细胞比值(neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio,NLR)=中性粒细胞计数/淋巴细胞计数;血小板-淋巴细胞比值(platelet-lymphocyte ratio,PLR)=血小板计数/淋巴细胞计数;淋巴细胞-单核细胞比值(lymphocyte-monocyte ratio,LMR)=淋巴细胞计数/单核细胞计数;全身免疫炎症指数(systemic immune-inflammation index,SII)=血小板计数×中性粒细胞/淋巴细胞计数;预后营养指数(prognostic nutritional index,PNI)=血清白蛋白水平+5× 外周血淋巴细胞计数;老年营养风险指数(geriatric nutritional risk index,GNRI)=1.489× 血清白蛋白水平(g/L)+41.7×(体重/理想体重),理想体重通常规定为体重指数(body mass index,BMI)为22 kg/m2时所对应的体重。

1.6 观察指标

1.6.1 术后病理学检查

根据标准[21]将病理学检查结果按照肿瘤退缩分级(tumor regression grade,TRG)分为5级:

TRG1:无癌细胞残留,由大量纤维化取代;TRG2:纤维化中散在少量癌细胞,残留癌细胞比例<10%;TRG3:纤维化多于残留癌细胞,残留癌细胞比例为10%~50%;TRG4:纤维化少于残留癌细胞,残留癌细胞比例 >50%;TRG5:无肿瘤退缩改变。将新辅助治疗+手术后的肿瘤标本内显示无癌细胞残留称为pCR;残留癌细胞比例≤10%称为MPR。pCR、MPR代表患者对于nICT具有较好的疗效,而TRG3 ~ 5代表患者接受新辅助治疗效果不佳。

1.6.2 新辅助治疗期间的药物相关不良反应

记录患者新辅助治疗期间的药物相关不良反应并根据常见不良反应评价标准(Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events,CTCAE) 4.0版[22]进行分级评估,分为1(轻)、2(中)、3(重)、4(威胁患者生命)和5级(与不良反应相关的死亡)。

1.6.3 新辅助治疗后手术的安全性评估

记录新辅助治疗后患者的R0切除情况、术中出血量、术后住院时间及术后并发症情况。

1.7 统计学处理

采用SPSS 26.0软件对数据进行统计分析。符合正态分布的计量资料以x±s表示,符合正态分布的计量资料多组比较采用方差分析及LSD-t检验进行事后检验;不符合正态分布的计量资料以M(P25,P75)表示,采用Mann-Whitney U检验;计数资料用n(%)表示,采用χ2检验,当不满足每个单元格数量>5时,采用Fisher精确检验。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 患者的基本特征

本研究共纳入62例患者,其中≥60岁的患者占67.7%,40~59岁的患者占32.3%;男性48例,女性14例;临床分期Ⅱ期为11.2%,Ⅲ期为51.6%,ⅣA期为37.1%。

2.2 术后病理学缓解情况

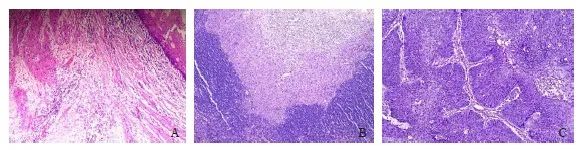

LAESCC患者行nICT+手术后共14例(22.58%)患者病理学缓解分级为TRG1,即达到pCR,pCR率为22.58%。LAESCC患者行nICT+手术后共11例(11.74%)患者病理学缓解分级为TRG2;共25例(40.32%)患者达到MPR,MPR率为40.32%。LAESCC患者行nICT+手术后共37例(59.68%)患者病理学缓解分级为TRG3~4,即治疗反应不佳。无术后病理学缓解分级为TRG5的患者。图1为TRG1、TRG2及TRG3~4组各1例患者术后肿瘤标本的镜下病理学图片。

图1 不同病理学缓解程度的患者镜下病理学图片

Fig. 1 Microscopic pathology picture of patients with different levels of pathologic remission

A: Microscopically, no distribution of tumor cells was seen, and the esophagus was structurally normal, with a complex flat epithelium in the mucosa and connective tissue in the submucosal layer, slight edema, and a high distribution of inflammatory cells. No other obvious pathologic changes were seen (H-E staining, ×40). B: Microscopically, a small number of incompletely differentiated squamous epithelioid tumor cells were seen in an amorphous distribution, loosely arranged and disordered, with pale stained cytoplasm. The surrounding blood vessels and connective tissue were hyperplastic, accompanied by a large number of inflammatory cells infiltration. On the other side, a large number of lymphocytes were also seen, which were densely arranged (H-E staining, ×40). C: Microscopically, large squamous epithelioid tumor cells were seen to be distributed, forming multiple finger-like projections with fibrovascular axes, and the tumor cells were arranged in an orderly fenestrated structure similar to that of the normal esophageal mucosa, but with a loss of cellular polarity, with nuclear schizophrenia prevalent, and surrounded by a scattering inflammatory cell infiltrate (H-E staining, ×100).

2.3 新辅助治疗的安全性评估

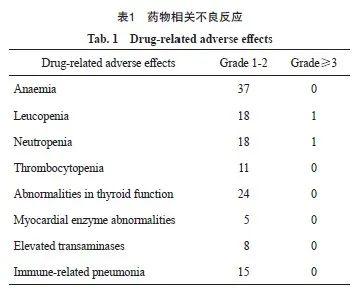

患者新辅助治疗期间的相关不良反应主要表现在骨髓抑制方面,集中在1~2级,仅1例患者的白细胞减少及中性粒细胞减少表现为4级;免疫治疗相关性肺炎及甲状腺功能改变均为1~2级,表现为轻症,新辅助治疗结束后随访期间均恢复至正常范围(表1)。

2.4 新辅助治疗后手术的安全性评估

62例患者经nICT后行根治性手术治疗,结果显示,61例患者R0切除,R0切除率为98.39%,手术时间为(222.16±62.91)min,术中出血量为(113.05±133.76)mL,术后住院时间为(9.95±4.04)d,术后1例患者出现吻合口瘘,1例出现皮下气肿,1例出现呼吸衰竭,14例出现肺部感染。

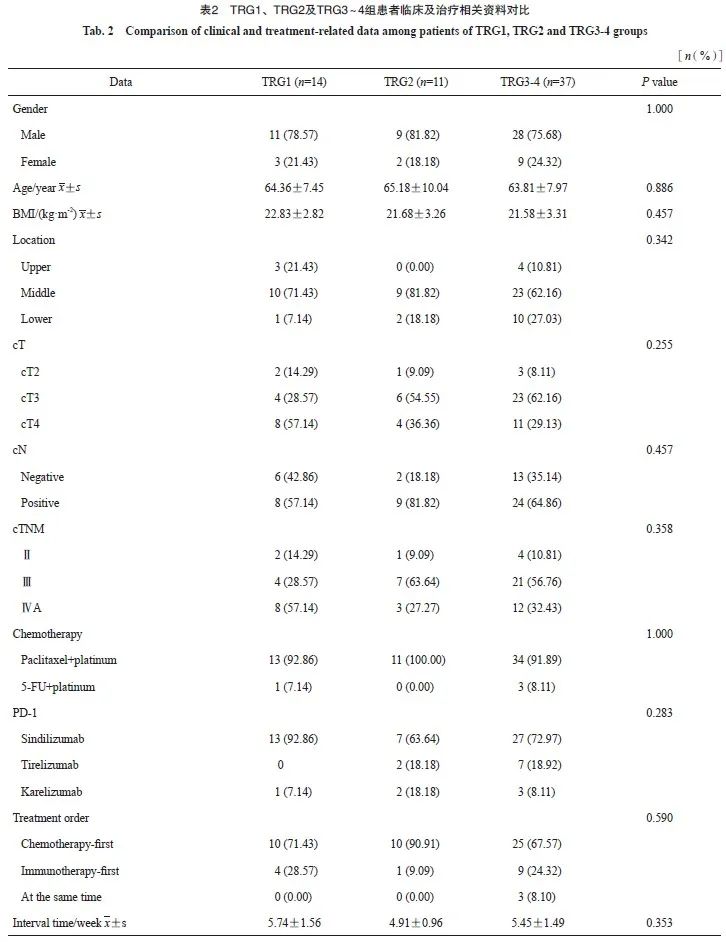

2.5 临床资料对比结果

TRG1、TRG2及TRG3 ~ 4组患者在性别、年龄、吸烟史、饮酒史、高血压史、糖尿病史、 BMI、肿瘤部位、临床分期、化疗方案、PD-1种类、化疗及免疫治疗使用顺序、新辅助治疗结束至手术的间隔时间等相关因素中的差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05,表2)。

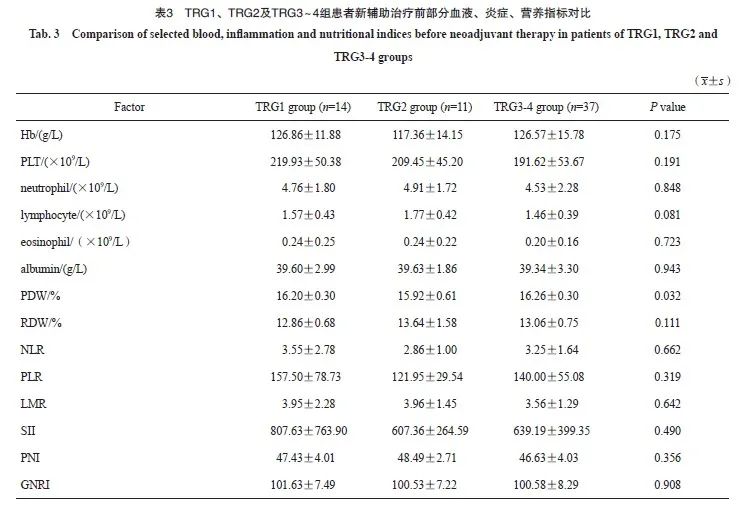

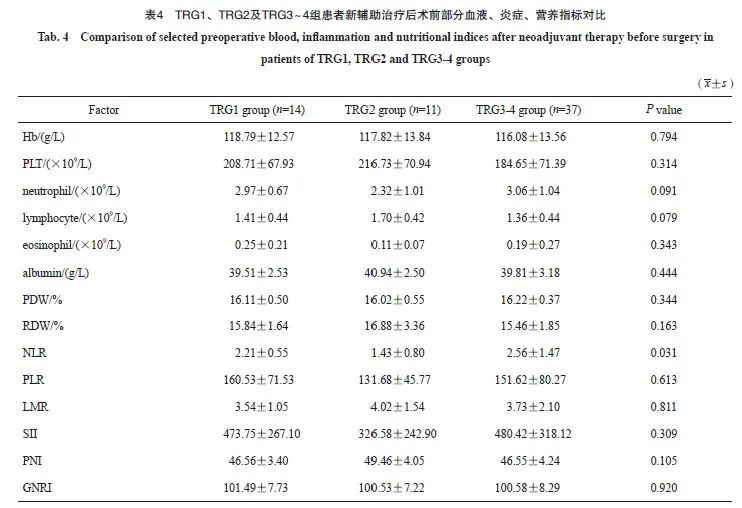

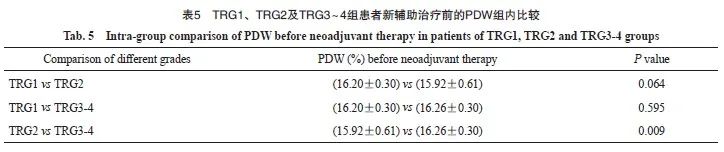

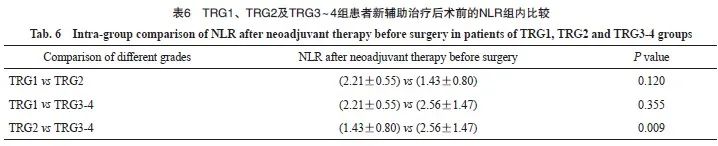

TRG1、TRG2及TRG3 ~ 4组患者在新辅助治疗前的血小板分布宽度(platelet distribution width,PDW)及新辅助治疗后术前的NLR差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),其余新辅助治疗前后的白细胞、血小板、中性粒细胞、红细胞、血红蛋白、嗜酸性例细胞、单核细胞等血液、炎症及营养学指标差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,表3、4)。

对TRG1、TRG2及TRG3~4组患者在新辅助治疗前的PDW及新辅助治疗后术前的NLR分别进行组内两两比较,发现TRG2组的PDW及NLR低于TRG3~4组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05,表5、6)。

3 讨 论

本研究中LAESCC患者nICT后行根治性手术治疗,患者的总体耐受性较好,大多数患者的药物相关不良反应≤2级,仅1例患者出现了严重的4级骨髓抑制,通过及时的对症处理,并未影响患者的整体治疗。在外科手术方面,62例患者中仅1例为R1切除,其余均为R0切除,R0切除率为98.39%。将本研究与川北医学院附属医院之前针对LAESCC患者新辅助化疗后手术治疗的研究[23]进行比较,发现手术时间[(222.16±62.91)min vs (245.40± 16.30)min]、术中出血量[(113.05± 133.76)mL vs(305.70±49.40)mL]、术后住院时间[(9.95±4.04)d vs(12.2±2.6)d]及手术并发症等方面未见明显差异,说明nICT较常见的新辅助化疗并未增加手术的风险,且通过nICT使肿瘤体积缩小,提高了R0切除率,证明在新辅助化疗的基础上联合免疫治疗是安全可行的。中国多项临床研究 [24-26]结果显示,接受nICT的LAESCC患者术后的pCR率为20%~50%,MPR率约在40%以上,且达到pCR/MPR对患者的生存预后产生了积极影响。本研究新辅助治疗后的病理学缓解率符合真实世界的数据研究结果。

越来越多的证据[27-30]表明,全身炎症反应和营养状况与肿瘤的发生有关并能够影响预后,许多炎症及营养相关指标如PNI、GNRI、NLR、PLR及LMR等在间接反映肿瘤患者免疫状态的同时也能在一定程度上预测患者的疗效及预后。既往研究[31-32]表明,炎症在癌症发展、疗效和长期生存中发挥关键作用。癌症相关性炎症可引起DNA损伤,促进血管生成和细胞增殖,抑制抗肿瘤免疫,并影响对抗癌药物的反应[33-34]。此外,炎症反应可能有助于诱导某些肿瘤干细胞群体,其对于肿瘤组织的抗性和转移至关重要[35]。中性粒细胞和淋巴细胞是炎症反应的重要组成部分,肿瘤浸润性中性粒细胞可能通过促进血管生成、细胞移动性和细胞迁移而与不良预后相关[31],而淋巴细胞与肿瘤细胞去除和改善肿瘤监视有关。较高的中性粒细胞数量及较低的淋巴细胞数量一定程度上表示机体处于免疫抑制状态,有研究[36-37]显示,NLR升高与多种肿瘤的预后不良相关,其可以作为一种肿瘤预后的生物标志物。NLR和其他血液学参数已成为预测不同类型癌症的总生存期(overall survival,OS)以及化疗或ICI治疗效果的生物标志物[38-40]。Wu等[41]回顾性分析了ESCC患者的外周血指标包括NLR、PLR、单核细胞-淋巴细胞比值(monocyte-lymphocyte ratio,MLR)和SII在PD-1抑制剂免疫治疗反应中的预测价值,结果显示,治疗后6周NLR低的ESCC患者的无进展生存(progression-free survival,PFS)率高于NLR高的患者(HR=2.097,95% CI:0.996~4.417,P=0.027),但基线时(HR=1.060,95% CI:0.524~2.146,P=0.869)或治疗后3周(HR=1.293,95% CI:0.628~2.663,P=0.459) NLR低的ESCC患者的PFS率与NLR高的患者相当。Chua等[42]研究发现,在转移性结直肠癌患者中,高NLR(>5)与OS降低独立相关,此外还发现基线具有高NLR(>5)的患者,在1个周期的化疗后,NLR降低到5以下的患者相较于NLR仍然>5的患者PFS显著更长。与上述研究相似,本研究也发现,nICT后病理学缓解程度TRG2的患者NLR低于TRG3~4的患者,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),然而治疗前不同病理学缓解程度组的患者的NLR水平之间的差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),提示新辅助治疗后NLR越低预示着疗效越好。未来可以进一步研究NLR在食管癌nICT中的疗效预测价值。

血小板活化在肿瘤的发生、发展过程中起着重要作用。PDW作为血小板指标之一,不仅检测血小板体积异质性,而且还检测血小板反应性。最近的几项研究[43-45]表明,高PDW是黑色素瘤、喉癌和胃癌患者的不利预后因素。 Song等[46]研究了PDW在ESCC患者中的预后价值,结果显示,PDW≥13.4%的患者OS率和无病生存(disease-free survival,DFS)率均低于对照组(P<0.001),多变量分析显示,PDW与OS(HR=1.194,95% CI:1.120~1.273,P<0.001)和DFS(HR=2.562,95% CI:1.733~3.786,P<0.001)独立相关,表明PDW升高是ESCC患者预后不良的独立影响因素。本研究结果显示,在基线时病理学缓解程度为TRG2的患者PDW低于TRG3~4的患者,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),提示在基线时越低的PDW预示着疗效越好。未来还可以进一步研究PDW在食管癌nICT中的疗效预测价值。

对LAESCC患者使用ICI联合化疗的新辅助治疗时,根据既往研究[13,25,47],术前治疗通常每3周1次,共2个周期,然而,有两项使用3个周期治疗的研究[48-49]实现了更高的pCR率和MPR率。更多的治疗周期数是否能提高疗效并带来更高的病理学缓解率,以及是否会增加治疗相关不良反应仍无定论,未来还需要进一步进行探究。理论上,化疗可诱导淋巴细胞减少症并选择性地耗尽免疫抑制细胞[50],而ICI疗法可导致肿瘤特异性T细胞的增殖[51]。因此,在化疗后应用ICI疗法可以允许效应T细胞的增殖并且降低用化疗药物杀死肿瘤特异性T细胞的可能性,从而产生更好的抗肿瘤效果。在一项回顾性研究[52]中,对于难治性肺癌患者,化疗后1~10 d使用ICI优于化疗前或化疗同时使用ICI。此外,Xing等[53]研究显示,在食管癌的新辅助治疗中,化疗后序贯免疫治疗比化疗同步免疫治疗更有效。然而从几个目前报道pCR率较高的研究来看, NICE研究[54]在同1天使用卡瑞丽珠单抗联合卡铂和白蛋白结合型紫杉醇,pCR率达到39.2%, Keystone-001研究[55]使用帕博利珠单抗治疗在前、紫杉醇加顺铂在后的3个周期治疗,pCR率达到41.1%,MPR率达到72%。本研究结果提示免疫治疗与化疗的使用顺序并不是影响最终病理学缓解情况的因素,未来还需要进一步探索化疗与免疫治疗的最佳组合模式。

综上所述,LAESCC患者nICT后行根治性手术可提高R0切除率且安全可靠,并且具有较高的pCR率和MPR率,有助于改善患者的远期生存,新辅助治疗前患者的PDW越低或新辅助治疗后术前患者的NLR越低预示着越好的病理学缓解效果。未来需要进行多中心、更大样本量的研究来验证本研究结果,并希望能够找到更多更有效的疗效预测指标。

利益冲突声明:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

作者贡献声明:

廖梓伊:实验设计,实验操作,数据分析,文章撰写;

彭杨,曾蓓蕾,马影颖,曾丽,甘科论:实验操作,数据分析;

马代远:文章修改。

[参考文献]

[1] SUNG H, FERLAY J, SIEGEL R L, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249.

[2] SMYTH E C, LAGERGREN J, FITZGERALD R C, et al. Oesophageal cancer[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2017, 3: 17048.

[3] 刘宗超, 李哲轩, 张 阳, 等. 2020全球癌症统计报告解读[J]. 肿瘤综合治疗电子杂志, 2021, 7(2): 1-14.

LIU Z C, LI Z X, ZHANG Y, et al. Interpretation on the report of global cancer statistics 2020[J]. J Multidiscip Cancer Manag Electron Version, 2021, 7(2): 1-14.

[4]MALTHANER R, WONG R K S, SPITHOFF K, et al. Preoperative or postoperative therapy for resectable oesophageal cancer: an updated practice guideline[J]. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol), 2010, 22(4): 250-256.

[5]RICE T W, RUSCH V W, APPERSON-HANSEN C, et al. Worldwide esophageal cancer collaboration[J]. Dis Esophagus, 2009, 22(1): 1-8.

[6]ANDO N, KATO H, IGAKI H, et al. A randomized trial comparing postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil versus preoperative chemotherapy for localized advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus (JCOG9907)[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2012, 19(1): 68-74.

[7]SHAPIRO J, VAN LANSCHOT J J B, HULSHOF M C C M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2015, 16(9): 1090-1098.

[8]JOYCE J A, FEARON D T. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment[J]. Science, 2015, 348(6230): 74-80.

[9]KOJIMA T, SHAH M A, MURO K, et al. Randomized phase Ⅲ KEYNOTE-181 study of pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in advanced esophageal cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2020, 38(35): 4138-4148.

[10]KATO K, CHO B C, TAKAHASHI M, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma refractory or intolerant to previous chemotherapy (ATTRACTION-3): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2019, 20(11): 1506-1517.

[11]HUANG J, XU J M, CHEN Y, et al. Camrelizumab versus investigator’s choice of chemotherapy as second-line therapy for advanced or metastatic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCORT): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2020, 21(6): 832-842.

[12]DE CASTRO JUNIOR G, SEGALLA J G, DE AZEVEDO S J, et al. A randomised phase Ⅱ study of chemoradiotherapy with or without nimotuzumab in locally advanced oesophageal cancer: NICE trial[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2018, 88: 21-30.

[13]ZHANG Z Y, HONG Z N, XIE S H, et al. Neoadjuvant sintilimab plus chemotherapy for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a single-arm, single-center, phase 2 trial (ESONICT-1)[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2021, 9(21): 1623.

[14]LI C Q, ZHAO S G, ZHENG Y Y, et al. Preoperative pembrolizumab combined with chemoradiotherapy for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (PALACE-1)[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2021, 144: 232-241.

[15]SHAH M A, KENNEDY E B, CATENACCI D V, et al. Treatment of locally advanced esophageal carcinoma: ASCO guideline[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2020, 38(23): 2677-2694.

[16]LIN J W, HSU C P, YEH H L, et al. The impact of pathological complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of esophagus[J]. J Chin Med Assoc, 2018, 81(1): 18-24.

[17]CHEVROLLIER G S, GIUGLIANO D N, PALAZZO F, et al. Patients with non-response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation for esophageal cancer have no survival advantage over patients undergoing primary esophagectomy[J]. J Gastrointest Surg, 2020, 24(2): 288-298.

[18]AL-KAABI A, VAN DER POST R S, VAN DER WERF L R, et al. Impact of pathological tumor response after CROSS neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery on long-term outcome of esophageal cancer: a population-based study[J]. Acta Oncol, 2021, 60(4): 497-504.

[19]RICE T W, ISHWARAN H, FERGUSON M K, et al. Cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: an eighth edition staging primer[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2017, 12(1): 36-42.

[20]国家卫生健康委员会. 食管癌诊疗规范(2018年版)[J]. 中华消化病与影像杂志(电子版), 2019, 9(4): 158-192.

National Health Commission. Diagnostic and therapeutic criteria for esophageal cancer (2018 edition)[J]. Chin J Dig Med Imageology Electron Ed, 2019, 9(4): 158-192.

[21]MANDARD A M, DALIBARD F, MANDARD J C, et al. Pathologic assessment of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy of esophageal carcinoma. Clinicopathologic correlations[J]. Cancer, 1994, 73(11): 2680-2686.

[22]BASCH E. New frontiers in patient-reported outcomes: adverse event reporting, comparative effectiveness, and quality assessment[J]. Annu Rev Med, 2014, 65: 307-317.

[23]姚 鹏, 别 俊, 李俊峰, 等. 信迪利单抗联合白蛋白紫杉醇+奈达铂化疗用于局部晚期食管癌术前新辅助治疗的临床观察[J]. 四川医学, 2023, 44(6): 579-584.

YAO P, BIE J, LI J F, et al. Clinical observation of sintilimab combined with albumin-bound paclitaxel and nedaplatin in preoperative neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced esophageal cancer[J]. Sichuan Med J, 2023, 44(6): 579-584.

[24]WU Z G, ZHENG Q, CHEN H Q, et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy in locally resectable advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J]. J Thorac Dis, 2021, 13(6): 3518-3528.

[25]YANG W X, XING X B, YEUNG S J, et al. Neoadjuvant programmed cell death 1 blockade combined with chemotherapy for resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2022, 10(1): e003497.

[26]LIU J, LI J P, LIN W L, et al. Neoadjuvant camrelizumab plus chemotherapy for resectable, locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (NIC-ESCC2019): a multicenter, phase 2 study[J]. Int J Cancer, 2022, 151(1): 128-137.

[27]DENG J H, ZHANG P, SUN Y, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis[J]. J Thorac Dis, 2018, 10(3): 1522-1531.

[28]SUN Y G, ZHANG L F. The clinical use of pretreatment NLR, PLR, and LMR in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: evidence from a meta-analysis[J]. Cancer Manag Res, 2018, 10: 6167-6179.

[29] ZHANG H D, SHANG X B, REN P, et al. The predictive value of a preoperative systemic immune-inflammation index and prognostic nutritional index in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2019, 234(2): 1794-1802.

[30] OKADOME K, BABA Y, YAGI T, et al. Prognostic nutritional index, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and prognosis in patients with esophageal cancer[J]. Ann Surg, 2020, 271(4): 693-700.

[31] DONSKOV F. Immunomonitoring and prognostic relevance of neutrophils in clinical trials[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2013, 23(3): 200-207.

[32] BALKWILL F, MANTOVANI A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? [J]. Lancet, 2001, 357(9255): 539-545.

[33] KIDANE D, CHAE W J, CZOCHOR J, et al. Interplay between DNA repair and inflammation, and the link to cancer[J]. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol, 2014, 49(2): 116-139.

[34] MIERKE C T. The fundamental role of mechanical properties in the progression of cancer disease and inflammation[J]. Rep Prog Phys, 2014, 77(7): 076602.

[35] LABIANO S, PALAZON A, MELERO I. Immune response regulation in the tumor microenvironment by hypoxia[J]. Semin Oncol, 2015, 42(3): 378-386.

[36] MEI Z B, SHI L, WANG B, et al. Prognostic role of pretreatment blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in advanced cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 66 cohort studies[J]. Cancer Treat Rev, 2017, 58: 1-13.

[37] TEMPLETON A J, MCNAMARA M G, ŠERUGA B, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2014, 106(6): dju124.

[38] AKCE M, LIU Y, ZAKKA K, et al. Impact of sarcopenia, BMI, and inflammatory biomarkers on survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with anti-PD-1 antibody[J]. Am J Clin Oncol, 2021, 44(2): 74-81.

[39] SEKINE K, KANDA S, GOTO Y, et al. Change in the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio is an early surrogate marker of the efficacy of nivolumab monotherapy in advanced non-smallcell lung cancer[J]. Lung Cancer, 2018, 124: 179-188.

[40] XU J M, LI Y, FAN Q X, et al. Clinical and biomarker analyses of sintilimab versus chemotherapy as second-line therapy for advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a randomized, open-label phase 2 study (ORIENT-2)[J]. Nat Commun, 2022, 13(1): 857.

[41] WU X B, HAN R K, ZHONG Y P, et al. Post treatment NLR is a predictor of response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J]. Cancer Cell Int, 2021, 21(1): 356.

[42] CHUA W, CHARLES K A, BARACOS V E, et al. Neutrophil/ lymphocyte ratio predicts chemotherapy outcomes in patients with advanced colorectal cancer[J]. Br J Cancer, 2011, 104(8): 1288-1295.

[43] LI N, DIAO Z Y, HUANG X Y, et al. Increased platelet distribution width predicts poor prognosis in melanoma patients[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1): 2970.

[44] ZHANG H, LIU L, FU S, et al. Higher platelet distribution width predicts poor prognosis in laryngeal cancer[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(29): 48138-48144.

[45] CHENG S Q, HAN F Y, WANG Y, et al. The red distribution width and the platelet distribution width as prognostic predictors in gastric cancer[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2017, 17(1): 163.

[46] SONG Q, WU J Z, WANG S, et al. Elevated preoperative platelet distribution width predicts poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J]. Sci Rep, 2019, 9(1): 15234.

[47] DUAN H T, WANG T H, LUO Z L, et al. A multicenter singlearm trial of sintilimab in combination with chemotherapy for neoadjuvant treatment of resectable esophageal cancer (SIN-ICE study)[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2021, 9(22): 1700.

[48] DUAN H T, SHAO C J, PAN M H, et al. Neoadjuvant pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in resectable esophageal cancer: an open-label, single-arm study (PEN-ICE)[J]. Front Immunol, 2022, 13: 849984.

[49] YAN X L, DUAN H T, NI Y F, et al. Tislelizumab combined with chemotherapy as neoadjuvant therapy for surgically resectable esophageal cancer: a prospective, single-arm, phase Ⅱ study (TD-NICE)[J]. Int J Surg, 2022, 103: 106680.

[50] SALAS-BENITO D, PÉREZ-GRACIA J L, PONZ-SARVISÉ M, et al. Paradigms on immunotherapy combinations with chemotherapy[J]. Cancer Discov, 2021, 11(6): 1353-1367.

[51] TOPALIAN S L, TAUBE J M, PARDOLL D M. Neoadjuvant checkpoint blockade for cancer immunotherapy[J]. Science, 2020, 367(6477): eaax0182.

[52] YAO W, ZHAO X, GONG Y, et al. Impact of the combined timing of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and chemotherapy on the outcomes in patients with refractory lung cancer[J]. ESMO Open, 2021, 6(2): 100094.

[53] XING W Q, ZHAO L D, ZHENG Y, et al. The sequence of chemotherapy and toripalimab might influence the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in locally advanced esophageal squamous cell cancer-a phase Ⅱ study[J]. Front Immunol, 2021, 12: 772450.

[54] YANG Y, LIU J, LIU Z C, et al. Two-year outcomes of clinical N2-3 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy from the phase 2 NICE study[J]. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2024, 167(3): 838-847.e1.

[55] SHANG X B, ZHAO G, LIANG F, et al. Safety and effectiveness of pembrolizumab combined with paclitaxel and cisplatin as neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgery for locally advanced resectable (stage Ⅲ) esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a study protocol for a prospective, single-arm, single-center, open-label, phase-Ⅱ trial (Keystone-001)[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2022, 10(4): 229.